The NIH demonstrated that Linus Pauling was correct in his assessment of the need for higher doses of vitamin C. But, unfortunately, they claimed the opposite. So here, we continue to use their own data to illustrate how they misinformed people.

We can now consider how the NIH story continues to mislead the medical community about vitamin C. We reviewed in Part 1 how the body was supposed to be “saturated” at an intake of about 400mg daily. Instead, they claimed 200mg was nearly as good and recommended an RDA of only 200mg.

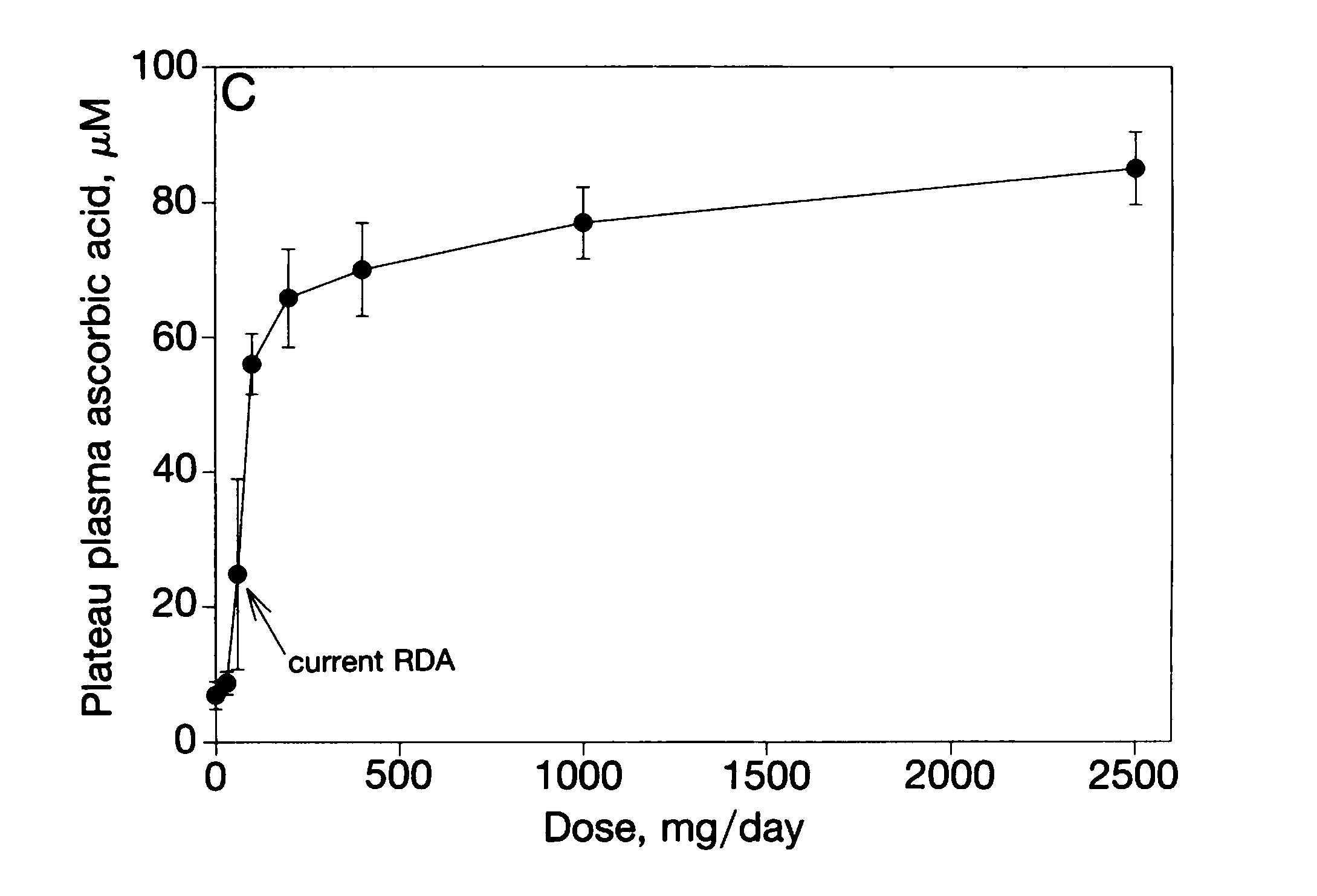

Looking again at the graph covered in Part One of this series of posts, we can see the blood levels increasing with dose and tailing off towards a maximum at higher doses. The NIH claimed that this showed the blood was “saturated” or reached a maximum blood level. We can estimate this maximum from this first graph at about 70-80 microM or more.

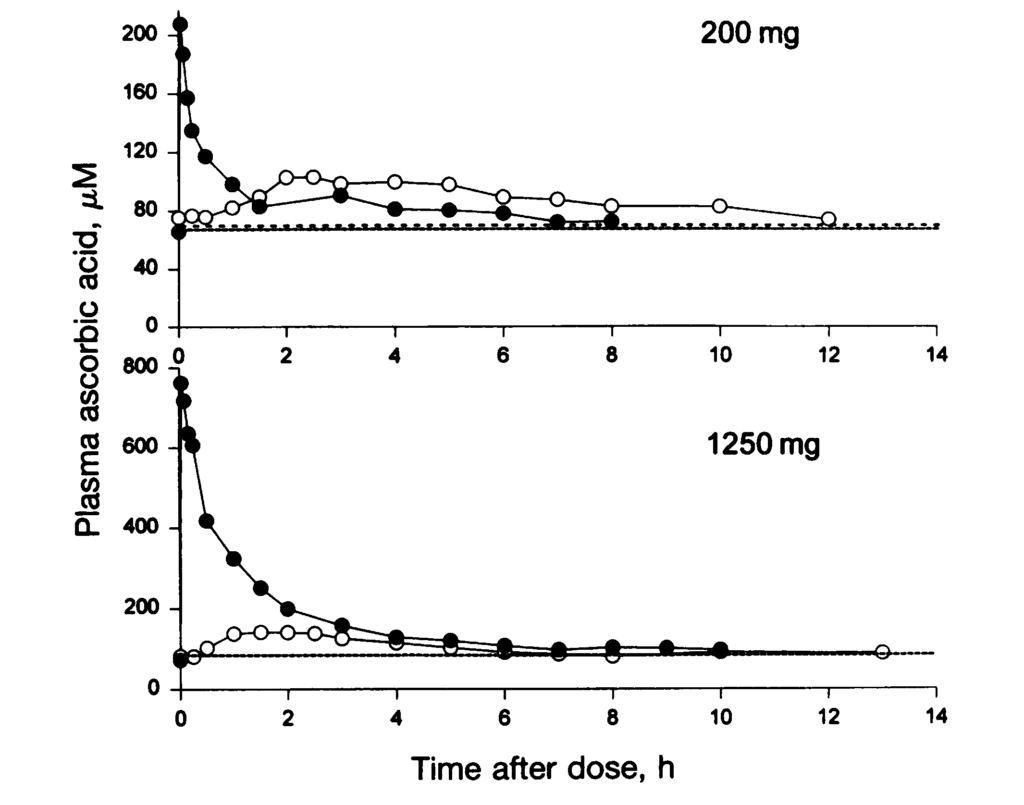

To get to the heart of the problem, we will simply state their error. The NIH gave a dose of vitamin C and waited until it had been excreted to measure the blood levels. Really. They gave some vitamin C and measured the blood levels 12 or more hours later. To make an analogy imagine giving someone a glass of water in the morning and asking if they were thirsty at the end of the day. Yes, you might conclude water does not help quench thirst.

Let that sink in. The NIH gave a dose, waited until it was eliminated and then measured the blood levels. When the level didn’t increase, they claimed it was “saturated” and all the body could absorb.

Here is another graph from Figure 1 in the paper.

Before we start, notice that the NIH “saturated” level (70-80) is a minimum rather than a maximum.

We will go through this Figure in some detail. However, the first thing to note is that 70-80 microM is the minimum of the data. The graphs’ baseline (solid and dashed) corresponds to the claimed “saturation”. In other words, the NIH declared that the minimum blood level they observed was the maximum. Let that sink in.

The NIH failed to notice that every data point was at or above their maximum. So instead, they took their claimed “saturation” point as the last data point they measured (12-13 hours after the dose).

Every measured blood level was at or above the so-called saturation level. An intelligent 10-year-old should not make this mistake.

OK, but we will simplify the explanation so the “experts” can grasp this error. First, we will estimate the half-life of vitamin C in the blood. Here we are using the NIH data, so there can be little controversy or scope for argument.

The Half-Life

The excretion half-life is how long it takes the kidneys to remove half the concentration in the blood. For example, penicillin has a half-life of around 1.5 hours and leaves the blood after about 8 hours. That’s why you take repeated doses. With this knowledge, a doctor might ask the patient to take one tablet every four hours to maintain the blood levels.

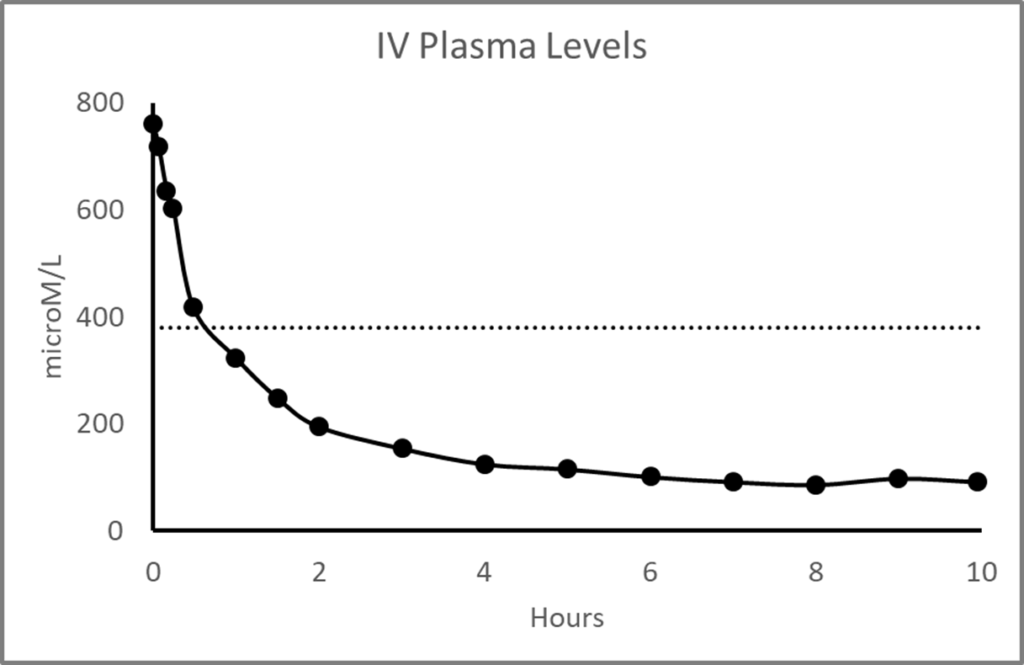

Here I have redrawn the data for a 1250mg injection from the lower graph. Again, the black disks indicate the IV doses.

To estimate the half-life a dose is injected, and the initial decay is measured. An injected dose is used as it quickly enters the blood over a second or two with the hypodermic push. Pharmacologists use the initial decline because the drug has less chance to move into the tissues and out again, which can lengthen the decay time and give an invalid estimate.

The dotted horizontal line indicates the first half of the decay. This decay takes about half an hour. So we can figure the excretion half-life of vitamin C in blood plasma is only about 30 minutes.

So the NIH gave a dose of vitamin C, waited for about 24 half-lives, and the levels didn’t go up? Nominally at that point, there would be only 1/224 or 1/16777216 of the dose remaining. The other earlier measurements they made were higher. Somehow they didn’t notice their “saturation” was a minimum rather than a maximum.

IV vs Oral

The NIH would later make a big deal about IV blood levels being higher than those obtained with oral supplementation. This difference is a general finding in pharmacology; when you push a drug into a vein using a needle, it gets in faster than if you take it as a tablet. Also, the oral dose is less absorbed as the gut retains some etc. In other words, a doctor expects an IV to produce higher blood levels.

I will come back to cover the effect of IV vs oral dose levels later in more detail. It will become evident that IV vitamin C is not a sensible approach to cancer. On the other hand, oral supplements have many advantages in chronic illness.

The NIH assume higher blood levels are more effective, but this assumption is naive. The biological effect results from concentration and duration, and IV levels are short-term. They will decay rapidly, as we have seen. A doctor can prolong the treatment by giving an infusion over several hours. We are still thinking short-term since a person can repeat oral doses maintaining a sustained blood level indefinitely.

Let’s take penicillin as an example. Penicillin has a short half-life, and doctors commonly prescribe repeated doses. The idea is to maintain an adequate blood level for an extended period. The aim is quite different to giving doses by injection. An injection produces a higher blood level for a short period. IV antibiotics are reserved mainly for acute infections in a hospital setting. They each have their purpose or use case. There would be no point in giving IV antibiotics for a chronic illness such as TB where the aim is to maintain multiple antibiotic pressure over months. If this treatment is intermittent rather than sustained, TB can become resistant to the antibiotic.

Two Responses To Vitamin C

The body has two uses for vitamin C. The first is to prevent scurvy. To achieve this benefit, we retain low doses for long periods. So an Elizabethan sailor might go three months without any vitamin C in apparent health. However, scurvy will eventually set in, and the sailor will sicken and potentially die. To prevent scurvy, we only need a few milligrams daily to maintain essential biochemistry.

The body retains vitamin C at low plasma levels below about 80 microM. The kidneys prevent excretion at or below the NIH “saturation” level. At these minimal levels, the vitamin is recycled and reused again and again. This minimum baseline is the NIHs “saturation” or maximum level.

The body actively uses energy to maintain a minimum amount of vitamin C to prevent acute scurvy. There may be multiple as yet unknown problems that would occur in the longer term, but scurvy is dramatic and deadly. We know that levels of about 80 microM, or more, are essential for health. Indeed, that was the philosophical basis of the NIH work. Moreover, evolution tells us that it is worth expending energy to keep the blood at this level which is thus a minimum. The resulting half-life is not well established but is about a month, which was fortunate for those early sailors.

In Part One, we estimated that the daily intake to maintain the baseline at its maximum was 2,500mg or above. These high intakes are what Linus Pauling was suggesting. Interestingly, a highly respected colleague of Pauling told me that Linus knew some early German results on doses and plasma levels. So he might have anticipated the NIH work and had the correct interpretation.

The second part of the body’s response is with higher doses and intakes. This response is for blood levels above the baseline. Sick people can absorb much more vitamin C. Dr Robert Cathcart and others clinically observed this. These levels are excreted rapidly and not reabsorbed by the kidneys. The vitamin enters the blood, and the kidneys remove it with a half-life of about half an hour. These higher levels of vitamin C serve a different purpose. Many doctors consider high levels increase resilience and resistance to disease. Nonetheless, the NIH avoided this whole area of vitamin C studies. They just told a story where high doses of the vitamin are not absorbed – a narrative without supporting data. The strange thing is the medical profession accepted this nonsense.

The following post will introduce oral doses.